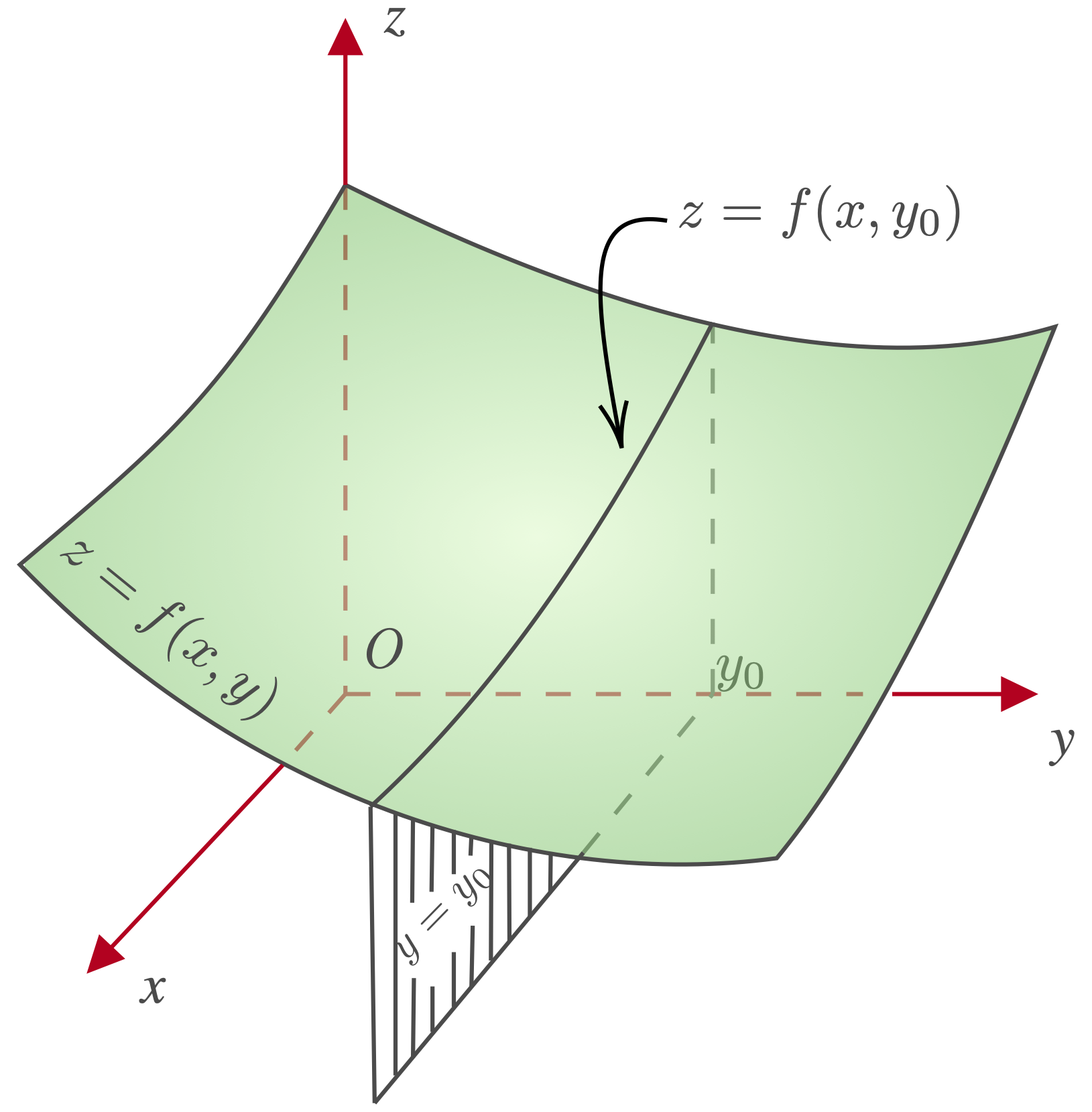

To determine how a function of several variables behaves when we change only one variable, we assign finite values to the other variables and allow only this variable to vary. In this case, the function becomes a function of a single variable. For example, consider a function $z=f(x,y)$, and assign to $y$ a (finite) fixed value of $y=y_0$. The result, $z=f(x,y_0)$, is a function of only $x$. The curve formed by the intersection of the surface $z=f(x,y)$ and the plane $y=y_0$ represents the graph of $z=f(x,y_0)$ (see Fig. 1). Now we can differentiate $z=f(x,y_0)$ like a function of a single variable. What we obtain is called the partial derivative of $f(x,y)$ with respect to $x$ at $(x_0,y_0)$:

$$\lim_{h\rightarrow 0}\frac{f(x_0+h,y_0)-f(x_0,y_0)}{h}.$$

To emphasize that we first held $y$ fixed at $y_0$ and then we differentiated with respect to $x$ at $x=x_0$, we use a “curved dee” $\partial$ instead of the regular letter $\text{d}$, and denote the above limit by $\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x_0,y_0)$.

|

| Figure 1: section of $z=f(x,y)$. |

From single variable calculus, we remember that the derivative is the slope of the tangent line. Here, the partial derivative of $f(x,y)$ with respect to $x$ is the tangent of the angle between the curve $z=f(x,y_0)$ and a line parallel to the $x$-axis at the point $\left(x_0,y_0,f(x_0,y_0)\right)$. That is, $\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x_0,y_0)$ is the slope of the surface $z=f(x,y)$ at $\big(x_0,y_0,f(x_0,y_0)\big)$ in the $x$ direction.

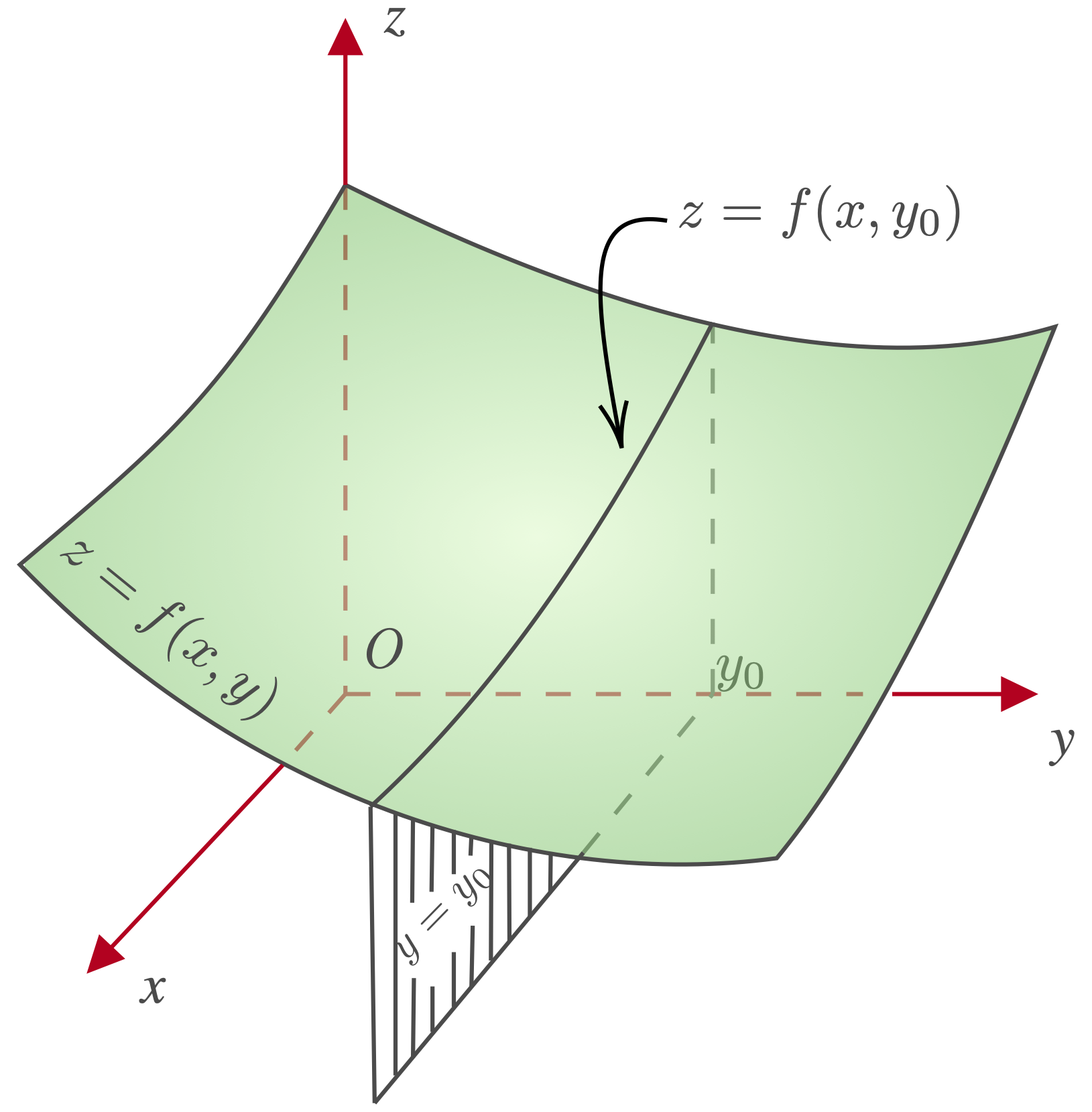

In a similar way, we can hold $x$ constant at $x_0$ and make $f$ a function of $y$ alone, the derivative of which is the partial derivative of $z=f(x,y)$ with respect to $y$ at $(x_0,y_0)$ and is given by:

$$\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(x_0,y_0)=\lim_{k\rightarrow 0}\frac{f(x_0,y_0+k)-f(x_0,y_0)}{k}.$$

$ \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x_0,y_0)$ is slope the slope of the surface $z=f(x,y)$ at $\big(x_0,y_0,f(x_0,y_0)\big)$ in the $x$ direction. See Fig. 2.

|

| Figure 2: section of $z=f(x,y)$ |

If we let $(x_0,y_0)$ vary in the domain of $f(x,y)$ and find the partial derivatives at all points, the partial derivatives become two functions of $x$ and $y$:

$$f_x(x,y)=\frac{\partial f(x,y)}{\partial x},\quad f_y(x,y)=\frac{\partial f(x,y)}{\partial y}$$

Definition 1: If $z=f(x,y)$, the first partial derivatives of $f$ with respect to the variables $x$ and $y$ are two functions $f_x(x,y)$ and $f_y(x,y)$ given by:

$$f_x(x,y)=\lim_{h\rightarrow 0}\frac{f(x+h,y)-f(x,y)}{h}$$

$$f_y(x,y)=\lim_{k\rightarrow 0}\frac{f(x,y+k)-f(x,y)}{k}$$

provided the limits exist.

- Other common notations of partial derivatives are

\begin{align*}

\frac{\partial f(x,y)}{\partial x}=&\frac{\partial}{\partial x}f(x,y)=\left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\right)_y=f_x(x,y)=f_1(x,y)=D_x f(x,y)=D_1 f(x,y)\\

=&\frac{\partial z}{\partial x}=z_x(x,y)=\partial_x f(x,y)=\partial_x z,\\

\frac{\partial f(x,y)}{\partial y}=&\frac{\partial}{\partial y}f(x,y)=\left(\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\right)_x=f_y(x,y)=f_2(x,y)=D_y f(x,y)=D_2 f(x,y)\\

=&\frac{\partial z}{\partial y}=z_y(x,y)=\partial_y f(x,y)=\partial_y z

\end{align*}

- Other common notations, specially in physics and mechanics, are $f’_x(x,y)$ or $f_{,x}(x,y)$. Comma or prime is used to emphasize that $x$ is not a subscript.

- If $u=f(x,y,z)$ is a function of $x,y$ and $z$, the first partial derivatives of $f$ with respect to $x, y$, and $z$ are:

\[ \bbox[#F2F2F2,5px,border:2px solid black]{\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x}=\lim_{h\to 0} \dfrac{f(x+h,y,z)-f(x,y,z)}{h}}\]

\[ \bbox[#F2F2F2,5px,border:2px solid black]{\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y}=\lim_{k\to 0}\dfrac{f(x,y+k,z)-f(x,y,z)}{k}}\]

\[ \bbox[#F2F2F2,5px,border:2px solid black]{\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial z}=\lim_{p \to 0}\dfrac{f(x,y,z+p)-f(x,y,z)}{p}}\]

- In general, if $u=f(x_1,x_2,\cdots,x_n)$ is a function of several variables, we can similarly define its partial derivatives by:

\[ \bbox[#F2F2F2,5px,border:2px solid black]{\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x_k}=\displaystyle{\lim_{h\rightarrow 0}}\dfrac{f(x_1,\cdots,x_{k-1},x_k+h,x_{k+1},\cdots,x_n)-f(x_1,\cdots,x_k,\cdots,x_n)}{h}}\]

- To calculate $\partial f/\partial x_k$, we differentiate with respect to $x_k$ in a regular way and deal with the other variables as if they are constants.

- To indicate that a partial derivative of $z=f(x,y)$ has been evaluated at $(x_0,y_0)$, we write:

$$\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(x_0,y_0)\quad\text{or}\quad \left.\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\right|_{(x_0,y_0)}\quad\text{or}\quad \left.\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}\right|_{{x=x_0} \atop {y=y_0}}\quad \text{or}\quad f_x(x_0,y_0) \quad \text{or}\quad z_x(x_0,y_0).$$

In the above notations we can replace $\partial f/\partial x$ with $\partial z/\partial x$.

Examples

Example 1

If $f(x,y)=x^2 \sin (xy)$, find $\partial f/\partial x$ and $\partial f/\partial y$.

Solution

To calculate $\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}$ we think of $y$ as a constant and differentiate with respect to $x$ as the only variable. Similarly to find $\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}$, we regard $x$ as a constant and differentiate with respect to $y$ as the only variable. Therefore:

$$\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}=2x\sin(xy)+x^2y \cos(xy) \quad \text{and} \quad \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}=x^3\cos(xy).$$

Example 2

If $z=x e^{y^2}$, find $\frac{\partial z}{\partial x}$ and $\frac{\partial z}{\partial y}$.

Solution

$$\frac{\partial z}{\partial x}=e^{y^2},\quad \frac{\partial z}{\partial y}=2xy e^{y^2}$$

Example 3

If $z=\arctan\left(\frac{y}{x}\right)$, find $\frac{\partial z}{\partial x}$ and $\frac{\partial z}{\partial y}$.

Solution

Finding partial derivatives in this example might look intimidating at first look. But if we remember what a partial derivative means, we can use the techniques for functions of single variable:

To calculate $\frac{\partial z}{\partial x}$, let $u(x)=y/x$ regarding $y$ as a fixed number. Using chain rule, we will have

$$\frac{\partial z}{\partial x}=\left(\frac{d}{du}\arctan(u)\right)\left(\frac{du}{dx}\right)$$

Recall that $\left(\frac{d}{du}\arctan(u)\right)=\frac{1}{1+u^2}$. Because $u'(x)=-y/x^2$, we can write

$$\frac{\partial z}{\partial x}=\left(\frac{1}{1+u^2}\right)\left(-\frac{y}{x^2}\right)=\frac{1}{1+\frac{y^2}{x^2}}\times\frac{-y}{x^2}=\frac{-y}{x^2+y^2}$$

Similarly by defining $v(y)=y/x$, and using chain rule, we will obtain

\begin{align*}

\frac{\partial z}{\partial y}=&\left(\frac{d}{dv}\arctan(v)\right)\left(\frac{dv}{dy}\right)\\

=&\frac{1}{1+v^2}\times\frac{1}{x}\\

=&\frac{1}{1+\frac{y^2}{x^2}}\times \frac{1}{x}=\frac{x}{x^2+y^2}

\end{align*}

Example 4

If $f(x,y)=x e^y+x^2y$, find $\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(1,0)$.

Solution

Method (a): First we hold $x$ fixed at $x=1$. Then we differentiate with respect to y and then plug $y=0$ in that:

$$f(1,y)=e^y+y\Rightarrow \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(1,0)=\left[ \frac{d}{dy}(e^y+y)\right]_{y=0}=\left[ e^y+1\right]_{y=0}=e^0+1=2.$$

Method (b): First we calculate $\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}$ similar to previous examples and then plug $x=1$ and $y=0$ in that:

$$\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}=x e^y+x^2\Rightarrow \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(1,0)=\left[x e^y+x^2\right]_{{x=1}\atop{y=0}}=1\times e^0+1^2=2.$$

Example 5

Find $\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(0,0)$ and $\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(0,0)$, if $f(x,y)$ is given by .

$$f(x,y)=\begin{cases}

\dfrac{x^2\cos x-y^2}{x^2+y^2} &\text{if } x\neq 0\\

0 & \text{if } x=0

\end{cases}$$

Solution

To calculate $\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(0,0)$, we plug $y=0$ in $f(x,y)$, and call the resulting function $g(x)$:

$$g(x)=f(x,0)=\begin{cases}

\cos x &\text{if } x\neq 0\\

0 &\text{if } x=0

\end{cases}$$

Because $\lim_{x\rightarrow 0}g(x)=\cos 0 =1$ is not equal to $g(0)=0$, $g(x)$ is not continuous at $x=0$ and consequently it is not differentiable at $x=0$. Therefore $\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(0,0)$ does not exist.

Similarly to calculate $\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(0,0)$, we plug $x=0$ in $f(x,y)$, which results in a constant function $h(y)=f(0,y)=-1$. Therefore

$\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(0,0)=h'(0)=0$.

Example 6

Find $\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(0,0)$ and $\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(0,0)$ if

$$f(x,y)=\begin{cases}

1-x-y & \text{if }y\geq 0\\

1-x^2-y^2 &\text{if } y<0

\end{cases}$$

Solution

To calculate $\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(0,0)$ we plug $y=0$, and find a function $g$ of $x$ alone:

$$g(x)=f(x,0)=1-x\Rightarrow \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}(0,0)=g'(0)=-1$$

Similarly for $\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(0,0)$ we plug $x=0$ and find

$$h(y)=f(0,y)=\begin{cases}

1-y & \text{if }y\geq 0\\

1-y^2 &\text{if } y<0

\end{cases}$$

where $h(y)$ is a function of single variable. We note that $h$ is continuous at $y=0$ because $\lim_{y\rightarrow 0^-} h(y)=\lim_{y\rightarrow 0+} h(y)=h(0)$. Also

$$h'(y)=\begin{cases}

-1 &\text{if } y> 0\\

-2y &\text{if } y<0

\end{cases}.$$

Because $h_-‘(0)=[-2y]_{y=0}=0$ and $h_+'(0)=1$ are not equal, $h(y)$ is not differentiable at $y=0$. Therefore, $\frac{\partial f}{\partial y}(0,0)$ does not exist. Graph of $h(y)$ is shown in Fig. 3.

|

| Figure 3 |

Example 6

Find the slopes in the $x$-direction and the $y$-direction of the surface given by

$$z=5-3x^2+\frac{y^2}{2}$$

at the point $(1,2,4)$

Solution

Recall that the slopes in the x-direction and the y-direction are $f_x$ and $f_y$. Therefore, we need to calculate $f_x(1,2)$ and $f_y(1,2)$.

$$f_x(x,y)=-6x,\quad f_y(x,y)=y$$

Thus, the slope of the surface at (1, 2, 4) in the $x$-direction and the $y$-direction are:

$$f_x(1,2)=-6\quad\text{slope in the $x$-direction}$$

$$f_y(1,2)=2\quad \text{slope in the $y$-direction}$$