In a great many practical problems, we want to find the least amount of time, least cost, greatest benefit, optimum size, etc. In such problems, which are called optimization problems, we look for the maximum or minimum value of a function and the particular value of the variable that gives such a value. In this section, we outline a strategy to systematically attack optimization problems by using differential calculus.

The graph of \(f\) is shown in Figure 1.

Because \(0\leq x\leq4\), the problem reduces to maximization of \(A(x)\) on the interval \([0,4]\). \[A'(x)=\sqrt{16-x^{2}}+x\frac{-2x}{2\sqrt{16-x^{2}}}.\] Setting \(A'(x)=0\), we obtain \[\sqrt{16-x^{2}}-\frac{x^{2}}{\sqrt{16-x^{2}}}=0.\] Multiplying both sides by \(\sqrt{16-x^{2}}\): \[16-x^{2}-x^{2}=0\] \[\Rightarrow x=\pm\sqrt{8}=\pm2\sqrt{2}.\] Only \(x=2\sqrt{2}\) is in the interval \([0,4]\). Therefore, the absolute maximum of \(A\) is one of the following numbers: \[A(0)=0,\quad A(4)=0,\] and \[A(2\sqrt{2})=\sqrt{8}\sqrt{16-8}=8.\] The above calculations show us that the rectangle of maximum area inscribed in the circle is a square with side lengths of \(\sqrt{8}=2\sqrt{2}\) and of area 8.

The graph of \(A\) is shown in Figure 3.

|

Figure 4

\(x=\) length of each side of the square

\(V=\) volume of the open box

We need to find a relationship between \(V\) and \(x\). Because the dimensions of the box are \(48-2x\), \(18-2x\), and \(x\) (Figure 6), the volume of the box is \[V=(48-2x)(18-2x)x=4x^{3}-132x^{2}+864x.\]

Because the dimensions of the box must be nonnegative, we have \[\begin{cases} 0\leq x\\ 0\leq18-2x & \Rightarrow\\ 0\leq48-2x \end{cases}0\leq x\leq9.\] Because \(V\) is continuous on the interval \([0,9]\), its absolute maximum occurs either at an endpoint \(x=0\), \(x=9\), or at a critical point. To obtain critical points \[\frac{dV}{dx}=12x^{2}-264x+864=0\] \[\Rightarrow x^{2}-22x+72=(x-4)(x-18)=0\] \[\Rightarrow x=4,\text{ or }x=18.\] However, \(x=18\not\in[0,9]\). Therefore, the only critical point in the interval \([0,9]\) is \(x=4\), and the absolute maximum of \(V\) is one of the following numbers.

| \(0\) | \(4\) | \(9\) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(V(x)\) | \(0\) | \(1600\) | \(0\) |

Therefore, the maximum volume is obtained when \(x=4\).

The graph of \(V(x)\) is shown in Figure 6.

To apply the First Derivative Test, we need to determine the sign of $f^\prime$:

| \(-\infty\) | \(-\sqrt{2}\) | \(0\) | \(\sqrt{2}\) | \(+\infty\) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sign of \(x+\sqrt{2}\) | \(- – -\) | \(0\) | \(+++\) | \(+\) | \(+++\) | \(+\) | \(+++\) | ||

| sign of \(x\) | \(- – -\) | \(-\) | \(- – -\) | \(0\) | \(+++\) | \(+\) | \(+++\) | ||

| sign of \(x-\sqrt{2}\) | \(- – -\) | $-$ | \(- – -\) | $-$ | \(—\) | \(+\) | \(+++\) | ||

| \(\therefore\) sign of \(f^\prime(x)\) | \(- – -\) | \(0\) | \(+++\) | \(0\) | \(—\) | \(0\) | \(+++\) | ||

| Increasing/Decreasing \(f(x)\) | \(\searrow\) | \(\nearrow\) | \(\searrow\) | \(\nearrow\) |

It follows from the First Derivative Test and the above table that \(x=0\) yields a local maximum, whereas \(x=\pm\sqrt{2}\) yield a minimum distance. \[\left.d\right|_{x=\pm\sqrt{2}}=\sqrt{2+(2-\frac{1}{2}2)^{2}}=\sqrt{3}.\]

Let’s see what will happen if we use the Second Derivative Test instead of the First Derivative Test \[f^{\prime\prime}(x)=x^{2}-2\] Because \(f^{\prime\prime}(0)=-2<0\), \(f\) has a local maximum at \(x=0\). Because\(f^{\prime\prime}(\pm\sqrt{2})=0\), the Second Derivative Test fails, and we cannot determine if \(f\) has a local maximum, a local minimum at \(x=\pm\sqrt{2}\).

Therefore, \(f(\pm\sqrt{2})=\sqrt{3}\) is the shortest distance from the point \((0,2)\) to the parabola \(8-x^{2}=2y\), and the closest points on the parabola to \((0,2)\) are \((\sqrt{2},3)\) and \((-\sqrt{2},3)\).

The graph of \(d=\sqrt{x^{2}+(2-x^{2}/2)^{2}}\) is shown in Figure 8.

Let’s summarize the strategy that we have applied to solve the examples of this section:

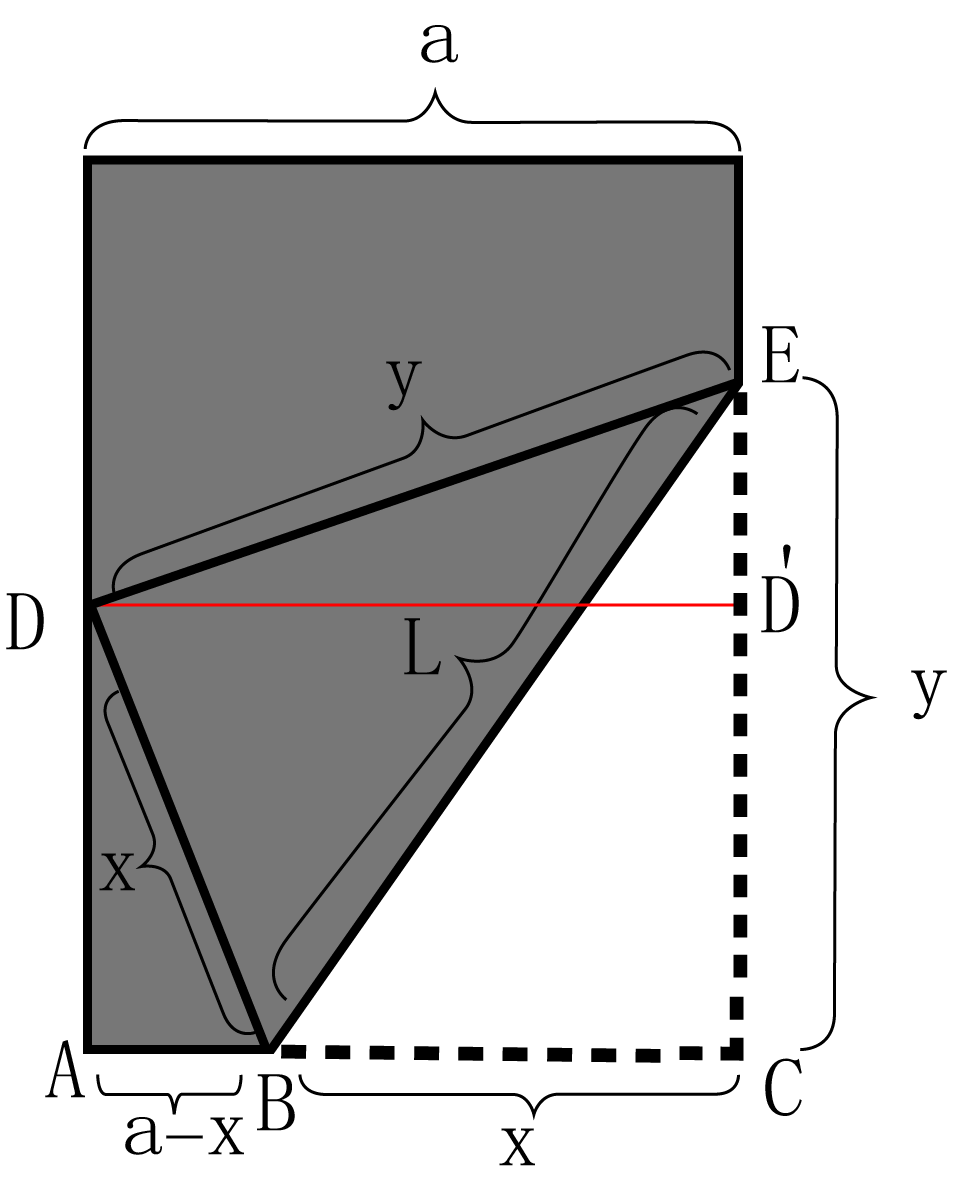

For example, in the last example, the primary equation is \(d=\sqrt{x^{2}+(y-2)^{2}}\). We needed to minimize \(d\) (or \(d^{2}\)), but \(d\) is a function of \(x\) and \(y\). So we had to eliminate one of the two variables using a secondary equation. Because \((x,y)\) is on the parabola, the secondary equation is the equation of parabola relating \(x\) and \(y\), which is \(2y=8-x^{2}\). \[\overset{\triangle}{OAB}\sim\overset{\triangle}{O’AB’}\] \[\Rightarrow\frac{AO’}{AO}=\frac{O’B’}{OB}\] or \[\frac{30-h}{30}=\frac{r}{18}\] \[\Rightarrow30(18)-18h=30r\] \[h=30-\frac{5}{3}r\tag{ii}\] Substituting (ii) into (i), we obtain \[V=\pi r^{2}\left(30-\frac{5}{3}r\right)=30\pi r^{2}-\frac{5}{3}\pi r^{3}.\] Now \(V\) is a function of \(r\) alone. Because \(r\) may vary only between 0 and 18 (the radius of the cone) \[0\leq r\leq18,\] and \(V\) is a continuous function, the existence of a maximum value is guaranteed. The maximum value occurs either at \(r=0\), \(r=18,\) or at a critical number. \[\begin{aligned} V'(r) & =60\pi r-5\pi r^{2}\\ & =5\pi r(12-r).\end{aligned}\] The solutions of \(V'(r)=0\) are \[r=0,\text{ }r=12.\] It suffices to compute \(V(r)\) at the critical numbers and the endpoints So the maximum volume occurs when \(r=12\) and \(h=30-\frac{5}{3}(12)=10\). The graph of \(V(r)\) is shown in Figure 11. From \(\triangle BCE\) \[L^{2}=x^{2}+y^{2}.\tag{i }\] We want to minimize \(L\), but \(L\) depends on two variables \(x\) and \(y\). To eliminate one of the variables, we need a relationship between \(x\) and \(y\). From \(\triangle BAD\), we have \[AB^{2}+AD^{2}=BD^{2}.\] Because before folding the page, \(\triangle BED\) was \(\triangle BEC\), we have \(BD=BC\) and thus \[(a-x)^{2}+AD^{2}=x^{2}\] \[\Rightarrow AD^{2}=x^{2}-(a-x)^{2}=2ax-a^{2}\] Because \(AD=CD’=2ax-x^{2}\), from \(\triangle DD’E\) \[DD’^{2}+D’E^{2}=DE^{2}\] and \[a^{2}+(y-AD)^{2}=y^{2}\] or \[a^{2}+(y-\sqrt{2ax-a^{2}})^{2}=y^{2}\] \[\Rightarrow-2y\sqrt{2ax-a^{2}}+2ax=0\] \[\Rightarrow y^{2}=\frac{a^{2}x^{2}}{2ax-a^{2}}=\frac{ax^{2}}{2x-a}\tag{ii}\] Substituting (ii) in (i) we obtain \[L^{2}=x^{2}+\frac{ax^{2}}{2x-a}.\] Instead of minimizing \(L\), we can minimize \(L^{2}\) to avoid differentiation of a radical. Let \[\begin{aligned} f(x) & =x^{2}+\frac{ax^{2}}{2x-a}\\ & =\frac{2x^{3}-ax^{2}+ax^{2}}{2x-a}\\ & =\frac{2x^{3}}{2x-a}.\end{aligned}\] The critical number (or critical point) of \(f\) is obtained by setting \(f^\prime(x)=0\): \[f^\prime(x)=\frac{6x^{2}(2x-a)-4x^{3}}{(2x-a)^{2}}=0\] \[\Rightarrow8x^{3}-6ax^{2}=2x^{2}(4x-3a)=0\] \[\Rightarrow x=0,x=\frac{3a}{4}.\] Note that \(x\) must be larger than \(a/2\), otherwise the expression under the radical \(L=\sqrt{2x^{3}/(2x-a)}\) becomes negative. Therefore, \(x=0\) is not acceptable. Because \((2x-a)^{2}>0\), the sign of \(f^\prime(x)\) is the same as the sign of its numerator, and the numerator \(8x^{3}-6ax^{2}=2x^{2}(4x-3a)\) is negative if \(x<3a/4\) and is positive if \(x>3a/4\). Therefore, by the First Derivative Test, \(x=3a/4\) is a local minimum point (\(f\) varies from a decreasing function to an increasing one), and \(L\) for \(x=3a/4\) is \[\left.\sqrt{\frac{2x^{3}}{2x-a}}\right|_{x=\frac{3a}{4}}=\frac{3\sqrt{3}}{4}a\approx1.299a.\] If \(x=a\), then \[L=\sqrt{\frac{2a^{2}}{2a-a}}=\sqrt{2}a\approx1.414a\] and \[\lim_{x\to a/2^{+}}L=\lim_{x\to a/2^{+}}\sqrt{\frac{2x^{3}}{2x-a}}\stackrel{\left[\frac{2a^{3}}{0^{+}}\right]}{=}+\infty.\] These calculations show that the absolute minimum of \(L\) is \(3\sqrt{3}a/4\). The graph of \(L/a\) versus \(x/a\) is shown in Figure 14. \[\begin{aligned} \frac{L}{a} & =\frac{1}{a}\sqrt{\frac{2x^{3}}{2x-a}}\\ & =\sqrt{\frac{2x^{3}}{a^{3}(2\frac{x}{a}-1)}}\\ & =\sqrt{\frac{2(x/a)^{3}}{2(x/a)-1}}\end{aligned}\] (b) The folded area \(A\) is \[A=xy\tag{iii }\] Substituting (ii) in (iii), we obtain \[\begin{aligned} A & =x\sqrt{\frac{ax^{2}}{2x-a}}\\ & =\sqrt{\frac{ax^{4}}{2x-a}}.\end{aligned}\] Again to avoid differentiation of a radical, we can minimize \(A^{2}\) instead of minimizing \(A\). So we minimize \[g(x)=\frac{ax^{4}}{2x-a}.\] The critical point is obtained by setting \[g^\prime(x)=\frac{4ax^{3}(2x-a)-2ax^{4}}{2x-a}=0\] \[\Rightarrow2ax^{3}\left[2(2x-a)-x\right]=0\] \[\Rightarrow x=0,x=\frac{2a}{3}.\] Again \(x=0\) is not within the domain of \(A\), which is the interval \((a/2,a]\). When \(x=2a/3\), the area is \[A=\frac{2a}{3}\sqrt{\frac{a\frac{4}{9}a^{2}}{\frac{4a}{3}-a}}=\frac{4a^{2}}{3\sqrt{3}}.\] We can show that \(A\to\infty\) as \(x\to+\infty\) or \(x\to a/2^{+}\), and \[\left.A\right|_{x=a}=a^{2}.\] Therefore, \(A\) has an absolute minimum when \(x=2a/3\). The graph of \(A/a^{2}\) versus \(x/a\) is shown in Figure 15. From \(\triangle ABC\): \[\tan\theta=\frac{b}{x}\] and from \(\triangle ADE\): \[\tan\theta=\frac{y}{a}.\] So the relationship between \(x\) and \(y\) is \[\frac{b}{x}=\frac{y}{a}\Rightarrow y=\frac{ab}{x}.\] Therefore, the length of the ladder can be expressed as \[\begin{aligned} L & =\sqrt{x^{2}+b^{2}}+\sqrt{\frac{a^{2}b^{2}}{x^{2}}+a^{2}}\\ & =\sqrt{x^{2}+b^{2}}+\sqrt{\frac{a^{2}b^{2}+a^{2}x^{2}}{x^{2}}}\\ & =\sqrt{x^{2}+b^{2}}+\frac{a}{x}\sqrt{b^{2}+x^{2}}\\ & =\sqrt{x^{2}+b^{2}}\left(1+\frac{a}{x}\right).\end{aligned}\] The critical point of \(L\) is obtained by setting \(dL/dx=0\): \[\begin{aligned} \frac{dL}{dx} & =\frac{2x}{2\sqrt{x^{2}+b^{2}}}\left(1+\frac{a}{x}\right)-\frac{a}{x^{2}}\sqrt{x^{2}+b^{2}}\\ & =\frac{1}{\sqrt{x^{2}+b^{2}}}\left[x+a-\frac{a}{x^{2}}(x^{2}+b^{2})\right]\end{aligned}\] \[\frac{dL}{dx}=0\Rightarrow x-\frac{ab^{2}}{x^{2}}=0\Rightarrow x=\sqrt[3]{ab^{2}}.\] and the minimum length \(L\) is \[\begin{aligned} \left.\sqrt{x^{2}+b^{2}}\left(1+\frac{a}{x}\right)\right|_{x=\sqrt[3]{ab^{2}}} & =\sqrt{a^{2/3}b^{4/3}+b^{2}}\left(1+\frac{a^{2/3}}{b^{2/3}}\right)\\ & =\sqrt{\frac{a^{2/3}b^{4/3}+b^{2}}{b^{4/3}}}\left(b^{2/3}+a^{2/3}\right)\\ & =(a^{2/3}+b^{2/3})^{3/2}.\end{aligned}\] Obviously as \(x\to0\) or \(x\to+\infty\), \(L\to+\infty\), and the local minimum of \(L\) is also its absolute minimum.

\(r=\) radius of the cylinder

\(h=\) height of the cylinder

\(V=\) volume of the cylinder

We know \[V=\pi r^{2}h,\tag{i}\] and we want to maximize \(V\) provided that the cylinder is inscribed in the cone. Here \(V\) depends both on \(r\) and \(h\) and it is necessary to express \(V\) in only one variable (either \(r\) or \(h\)). To do so, we look for a relationship that connects \(r\) and \(h\). If we look at the cone from the side, we realize that \(\triangle OAB\) and \(\triangle O’AB’\) are similar (Figure 10).

\(r\)

\(0\)

\(12\)

\(18\)

\(V\)

\(0\)

\(1440\pi\)

\(0\)

(a) Find the width of the part folded over when the length of the crease is a minimum,

(b) Find the width when the area folded over is a minimum.

\(x=\) length of \(BC\)

\(y=\) length of \(CE\)

\(L=\) length of \(BE\)